The front derailleur is not dead

‘One-by’ (or ‘1x’) bicycles with a single front chain-ring are increasingly popular. Not so long ago, mountain bikes would all have triple front chainrings. Now, barely any can be found […]

‘One-by’ (or ‘1x’) bicycles with a single front chain-ring are increasingly popular. Not so long ago, mountain bikes would all have triple front chainrings. Now, barely any can be found […]

“No one remembers who climbed Mount Everest the second time” -Sir Edmund Hillary This is the third iteration of the Smiths Everest (model reference: PRS-25) wristwatch. The first was a […]

Lightbulb moment on a BenQ Projector For some reason that escapes me at the moment, if only there was some media coverage, I seem to be at home more often […]

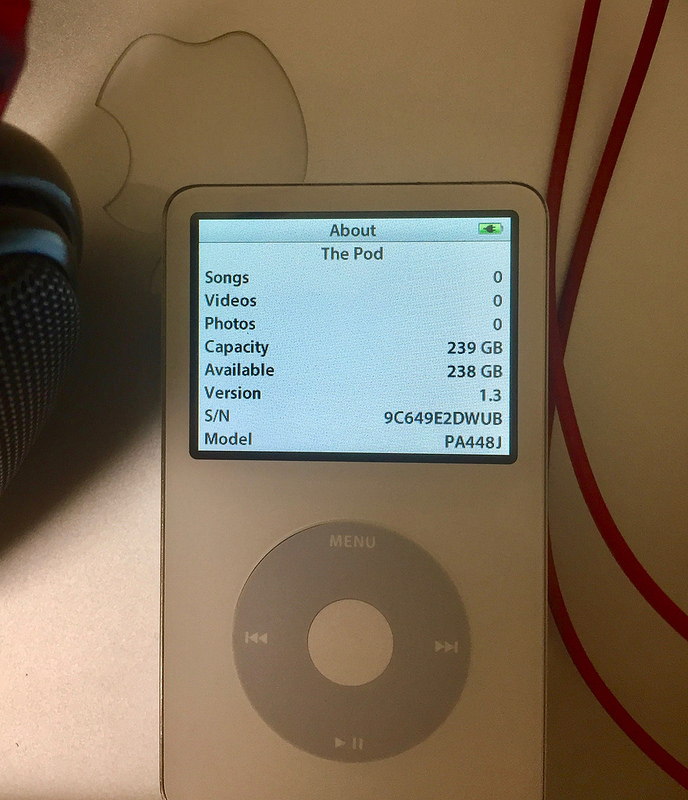

Having re-ripped my entire CD collection lossless, I needed more space on my ageing 2006 iPod. Apart from the disk capacity (80GB) it all worked fine, and this particular version […]

My Brompton needed a new front wheel, so I thought I’d replace it with one with a dynamo hub. I’d built one of these for my “normal” bicycle and liked […]

Once upon a time, Seiko released an unusual looking diver’s watch. That is, the watch was unusual, not that it was particularly suited to unusual-looking divers. That would have been […]