Once upon a time, Seiko released an unusual looking diver’s watch. That is, the watch was unusual, not that it was particularly suited to unusual-looking divers. That would have been too niche, even for Seiko. Who, it might be remembered, once made a watch boasting a handy drum machine.

The model was called SKX779, continuing Seiko’s admirable and long standing affection for randomly generated instantly forgettable model references. Debuting in 1996, it quickly made no impact whatsoever. I bought one though, and then another.

Despite having some more costly watches, I wore them both, a lot.

For fifty years or so, other watch manufacturers had continued trying to emulate Rolex’s iconic Submariner, mixing in a bit of Omega’s Seamaster here and Blancpain’s Fifty Fathoms there. Changing the bezel font or dial colour, perhaps releasing a special edition each year in a fancy box. The Swiss dive watch was tending towards uniformity. Many might feel it still is.

Whereas Seiko had always had their professional-targeted dive watches. Developed with real feedback from actual commercial divers, and subject to many many design patents. Even the curves on those rubber straps are patented Seiko designs, the exact radius of the curves worked out scientifically for purpose, not appearance.

These were serious, expensive, function-over-form tools. Here’s one, my SBBN013:

Somewhere south of these sat the SKX007 watch, the Volkswagen Beetle of divers. Everything you needed, ISO-certified, and for a reasonable price. A modest, capable and reliable instrument. The people’s dive watch. I have one and love it.

Then the SKX779 arrived like Mad Max’s less-introverted cousin…

The hands and dial markers were huge, with luminous material applied by trowel. In the dark, it glowed brighter than a salaryman’s cheeks after five large Asahi beers. The bezel was solid, with the minute markers carved in, and deep scalloped edges. No cheap aluminum insert. The bracelet was heavy stainless steel, the solid links held to the 42.3mm-wide case by massive 22mm springbars as though preparing for a Monster Truck tug of war.

The crown wasn’t some parts-bin choice either. It echoed the design of the bezel, including the scallops, and was unique to this model. The movement was Seiko’s own entirely in-house developed and manufactured 7S26, a proven automatic calibre built for longevity and reliability. It wound as soon as you picked it up. It would continue to run for decades with none of the Swiss neediness for expensive servicing and delicate handling.

It didn’t just not look like a generic dive watch, it looked like nothing else at all.

Later it would be released with an orange dial, and later still, with further colour variations in sometimes limited numbers. It was made in Singapore, or Thailand, or Malaysia and almost entirely by machines. Somewhere where manufacturing costs and exporting logistics were favourable. This meant that trading intermediaries could obtain supplies and sell on at retail for around $200, less than half its list price.

It was always a hard to find model in shops in Japan, despite its reputation as a “Japan Domestic Market” watch, but the internet solved that for everyone. It eventually became a popular, though oddball, choice among dive watch afficianados. It earned itself the “Monster” nickname on account of its heft and aggressive styling.

I used mine for hiking, climbing, diving, swimming, surfing… you name it.

On Mt Fuji, climbing in the dark, freezing in a snowstorm:

Better conditions, climbing in the Japan Alps. Legibility, reliability and toughness:

Close to the edge, on Mount Tanigawa. Deceptively perhaps the most dangerous mountain in the world:

A little scuba diving off Hawaii…

And using my orange Monster on Mt Asama, the most active volcano in mainland Japan:

On this particular day, it was so cold that my urine froze, my “freeze resistant” rugged camera shut down, and I couldn’t feel my fingers for a few days. The $200 monster, nonchalantly strapped to the outside of my Gore Tex sleeve, made no complaints and performed flawlessly.

Some years ago I posted on my very practical guide to spending $10,000 on a watch that one should buy a Seiko Monster to wear, and another to keep new-in-the-box as an investment. These original Monsters are discontinued now. You can still find new-in-box ones for sale from time to time in Japan, but expect to pay well over $1000. That’s a better return on investment in a few years than any Rolex.

And then…

The original SKX779 Monster was superceded in the 21st century by the SRP307 or second-generation model. This also came in a range of colours with a few other changes. Notably a new movement (4R36) in place of the 7S26. This offered the exciting novelty of being hand-windable, as well as “hacking”, the ability to freeze the movement of the seconds hand to enable precise time synchronisation. The dial markers became more aggressive still, resembling sharks teeth.

The seconds hand gained a bit of colour. The unique crown was lost though. I passed on this generation, but it’s a fine watch nonetheless.

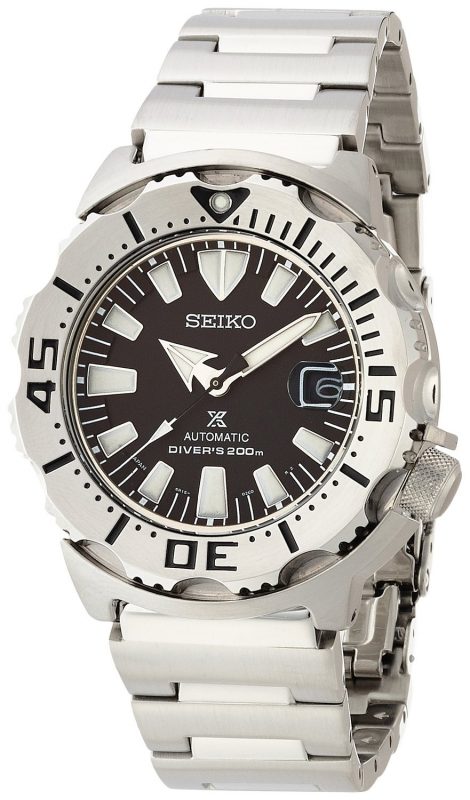

Then in 2014, the 3rd generation Monster was released. For those following along with Seiko’s naming convention, the SBDC025:

This was quite a change.

The 4R36 movement was replaced with an even higher specification 6R15 movement, previously only fitted to Seiko’s more upmarket models. This offered an increased power reserve of over 50 hours, accomplished by replacing the mainspring with Seiko’s newly developed proprietary “SPRON” cobalt/nickel/chromium alloy. The 6R15 retained the hacking and hand-winding capabilites of the 4R36 but lost the day indicator. In fact, while using upgraded materials and with some additional facilities, both the 6R15 and 4R36 share much of the basic 7S26 movement design heritage. This should ensure a reliable life.

The dial is also improved, now featuring less aggressive markers, surrounded by a thin metal border, as indeed are the hands. This is similar design language to the Rolex Submariner and its many imitators. Perhaps most obviously, the crystal now sports a cyclops magnifier over the date, reminiscent of, yes, the Rolex Submariner. Seiko’s branding is reinforced on the dial by the interlocking P and S in an X-like logo denoting “Prospex”. This is the model range Seiko describe as “serious watches for serious sports”.

The overall effect of these tweaks is to subtly but significantly lift the appearance of the Monster well above its original budget level.

Towards the end of 2016, a limited (1000 pieces) version named the SZSC003 was released, with a dark blue dial.

As with the SBDC version, this is made in Japan. The keen eyed will spot that the dial has “JAPAN” between the 7 and 8 markers, and the caseback also confirms the origin.

Unlike the Malaysian/Singaporean/Thai versions, it is thus not readily available to Asian distributors at a big discount. Which means it retails much closer to Seiko’s intended price ($500~) or about twice as much as its predecessors.

You’re going to need a bigger boat load of cash.

And so…

Has the 3rd generation Monster jumped the shark or grown up?

I’d defend the original, first generation Monster as an icon. Managing to provide startlingly original design and high quality execution in that most over-subscribed and under-imaginative genre, the dive watch. That the first generation is now fetching prices north of $1000 suggests collectors and history will agree. I described it in 2013 as refusing to better itself and “the only truly original dive watch created in the last 20 years […] the current equivalent of buying a military submariner for £350 back in the day”. Nothing has changed my opinion since. If you have one, keep it and enjoy it.

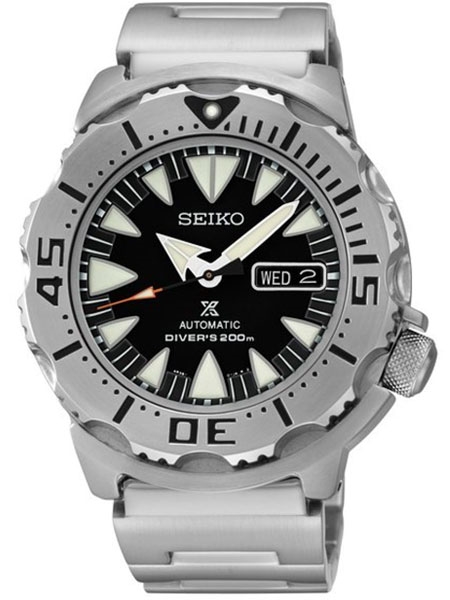

1st and 3rd generation Monsters compared:

The second generation lost some of the originality (the crown, in particular) and didn’t sufficiently make up for it elsewhere, in my opinion. The teenager, dropping the street clothes and trying on a suit for the first time. But not quite making it. You know the look.

The third generation though, seems at ease with itself.

Yes, it has tried to “better itself” and in particular those metal-outlined markers echo both Rolex and Omega dive watch language. But then, both of those marques’ original Submariners and Seamasters originally used basic unadorned markers. They too evolved. The Monster is no longer the rebel. It’s grown up. It now wears its fine tailoring with the quiet confidence of maturity.

If such a progression is, like age, inevitable, then I think the Monster has largely managed it successfully. And that is the most any of us can ask.

Great work on this article! If you don’t mind me asking, where did you find the production number for the szsc003? I just purchased one!